The Commission

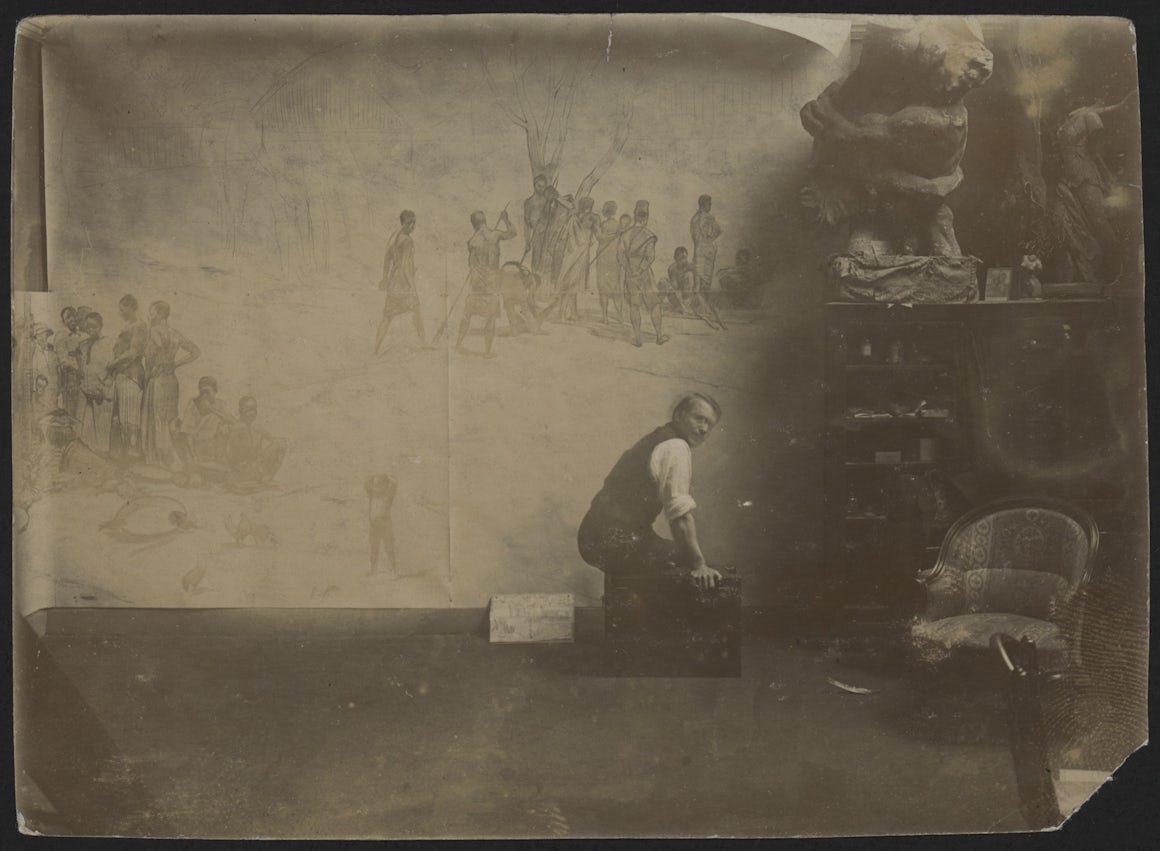

In 1911, the Belgian Minister of Colonies, Jules Renkin, commissioned the Panorama from the Belgian painters Paul Mathieu (1872-1932) and Alfred Bastien 1873-1955). These painters were well known participants of the Salons – or public art exhibitions – but it was the first time they had worked on such a large scale. To prepare for this task they undertook an eight-week mission to Congo, sponsored by the recently established Artistic Mission Travel Bursary program of the Ministry of Colonies. During this trip, they travelled to different parts of Congo and made numerous sketches, study paintings and photographs.

Based on this experience and the materials they assembled, they created the Panorama of Congo, initially in the form of sketches that were approved by the Ministry, and then in painted form. The canvas is 115 meters by 14 meters, which makes for a surface of 1610m2. The painters were also responsible for creating a so-called ‘faux terrain’, a three-dimensional landscape between the painting and the central viewing platform. This consisted of bushes, plants, rocks, gravel and sand as well as painted cut-out figures, adding to the immersive experience of the viewer.

The Pavilion

The painting was exhibited in the ‘Congo Pavilion’, a large rotunda designed by the Belgian architect Jean Joseph Caluwaers (1863-1948). Viewers experienced the Panorama from an elevated central platform and were thus surrounded by the painting. A large canopy suspended from the ceiling filtered daylight coming in through the glass roof which gave the painting a more naturalistic look.

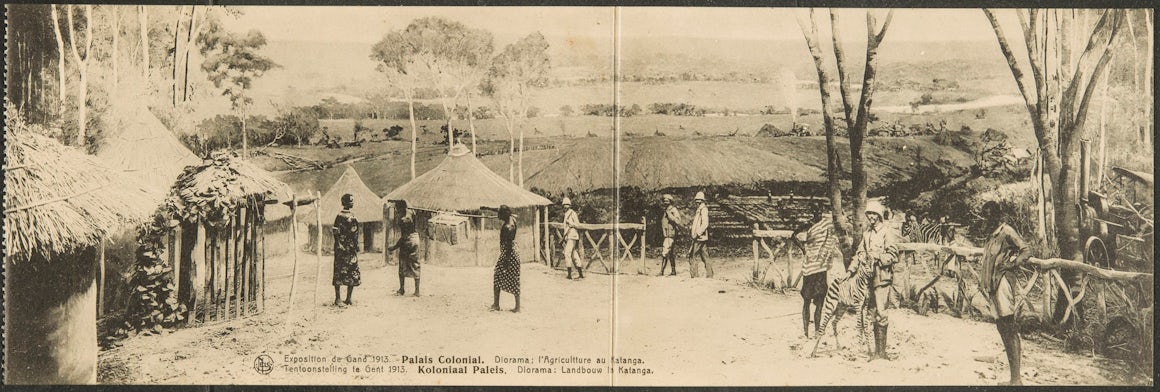

The pavilion also housed four large-scale dioramas (6.5 x 10 meters) by the same painters. These represented the palm oil industry, the Cockerill ship wharf and steam ship service from Belgium to Congo, official agricultural initiatives in the Katanga area and Catholic missionaries. Exhibitions on agriculture and colonial wares featured in two large exhibition halls in the same building.

Set of 4 panoramic postcards of the dioramas exhibited alongside the Congo Panorama in the colonial pavilion in 1913. (Published by Nels, Brussels. 1913. Private collection)

The Painting

The Panorama consists of eight scenes. The main focus is Matadi, the furthest inland port of the Congo Free State and the terminus for international ships entering the African continent via the Congo river. It was therefore a gateway into the heart of Africa.

Three of the painting’s scenes focus on Matadi — the Port and Station, a view of the village, and the Indigenous Market. The other scenes correspond to the outskirts of Matadi: Leopold’s Ravine; Pic Cambier; and rapids on the river M’Pozo. The Panorama also visualizes places far from Matadi, specifically the rainforest – which was 1500 kilometres away – and the village of Kinshasa showing a scene of people dancing next to a giant Baobab. Despite being presented as such, these eight scenes are not geographically continuous in reality. This makes the Panorama a kind of cappricio, an imaginary landscape consisting of different elements.

The Panorama was painted in a modern realist style which was en vogue at the time. Despite its realist ambitions what we see is an artistic interpretation of two painters with an interest in color schemes, composition, pictorial traditions in landscape and portrait painting.

(below) Luxury folder with reproductions of the Panorama published on occasion of the World Exhibition in Ghent, 1913. (Le Congo Belge. Reproduction en neuf estampes du Panorama Colonial de Paul Mathieu et d’Afred Bastien. Publié sur le patronage du Ministère des Colonies (1913). Bruxelles : Editions d’Art Eugène Mertens)

An imperial phantasy – is this more Colonial Propaganda?

According to the visitor’s guide, the painting demonstrated the sharp contrast between the Congo Free State as “the Belgians found it” in the late 19th century, and the country it became under colonial rule.. The image clearly serves Belgium’s imperialist agenda and presents the ‘Belgian Congo’ as a colonial Eldorado, an imperialist fiction.

The Belgian Government badly needed a sanitized imagelike this one. Belgium’s custody over Congo was recent and came in the wake of international outrage once the atrocities of King Leopold’s exploitation of the Congo had been exposed. In 1908 the Congo Free State was transferred to the Belgian government and became an official Belgian colony. The International Exposition in Ghent was the first official, large-scale effort to promote this newly acquired colony and the stakes were high. On an international level, Belgium had to demonstrate that the dark days of the Congo Free State had ended; while on the national level, the government had to secure the support of Belgian citizens. The Panorama therefore offers a window onto Belgium’s imperial vision, intertwined with the country’s economic and political agenda.

The Colonial Gaze

The choice of the Belgian Government to present its colony in a panoramic form was hugely significant. Audiences were accustomed to consuming panoramic views as aligned with colonial agendas. Presenting an immersive and supposedly comprehensive image representing the vastness of the Congolese territory, symbolized its aesthetic and material availability for those with a colonial gaze. It conveyed the message that Congo could be conquered and mastered and this feeling would have been experienced by the viewers on the platform. As long as the audience stayed on the platform and viewed the painting from a prescribed position, this illusion was perpetuated. The Panorama therefore becomes an ideological ‘weapon’ and tool for geopolitical ambitions.

The relationship between the Panorama’s and imperialism is inextricable. It symbolized the center-periphery dynamic and power (un)balances at the core of colonial ideology. Through analyzing and deconstructing this painting and its context, the violence and legacy of colonial expansion is exposed and ‘hidden’ histories resurface.